IN CONVERSATION WITH MIKE HURLEY: BELFAST’S COLONIAL THEATRE

Nov/Dec 2022

Interview & Photographs by Devon Harris

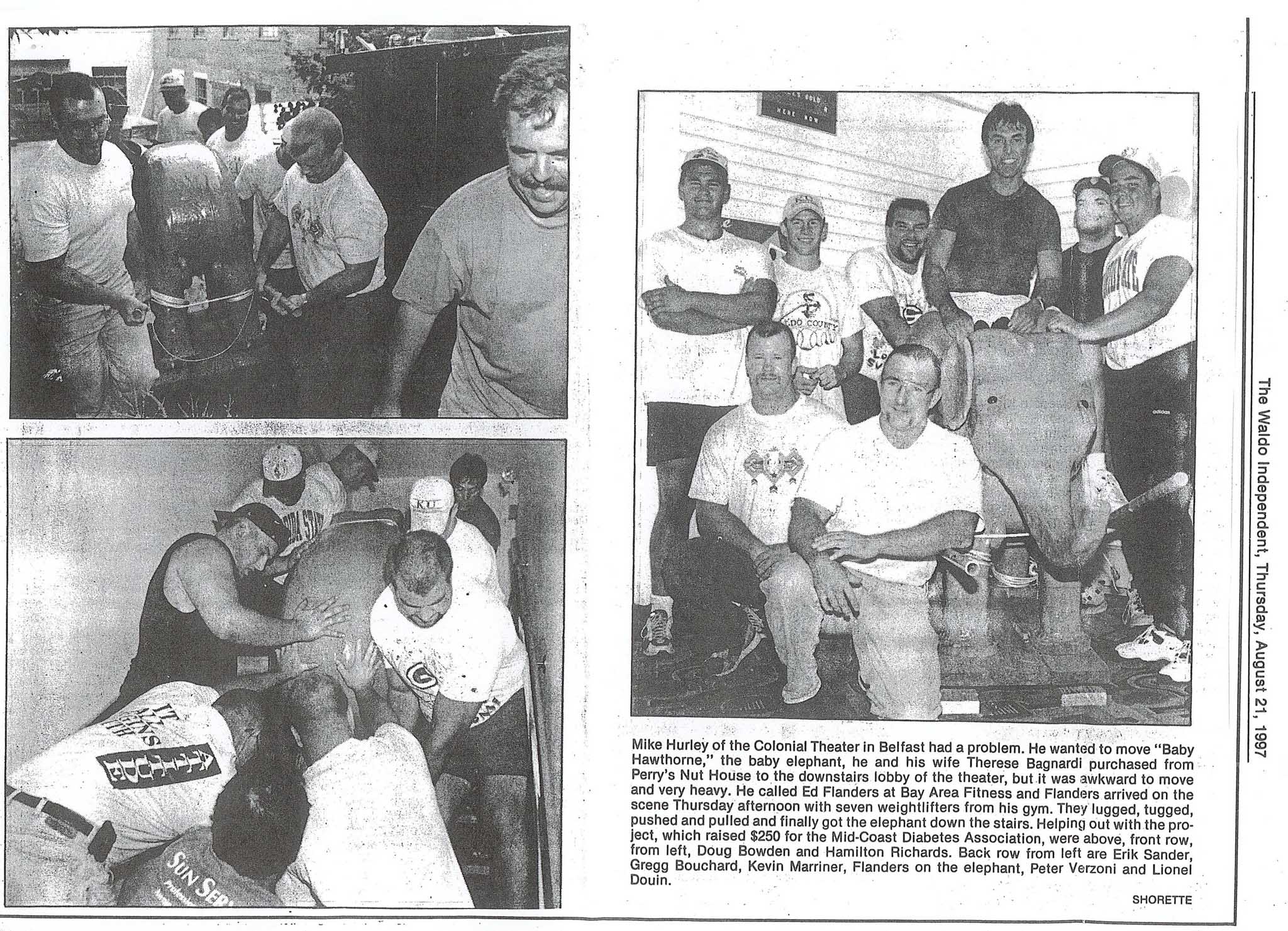

Mike Hurley and Therese Bagnardi bought the Colonial Theatre in 1995 and ran it for 27 years before putting it up for sale again this September. I moved to Belfast during the pandemic, when the Colonial—along with most other theaters across the country—was closed to the public. A year later, when I heard of its impending closure, I vowed to make it in for a show while I still could, and ended up at the last showing of the last movie, on the final night of the 10 days of free movies that Mike and Therese closed with.

It’s a bittersweet feeling to stand in the midst of an ending. The room was packed, and as I sipped my beer I listened to groups of people around me telling their own personal stories of the Colonial. First jobs, first dates, favorite movies …. While I didn’t grow up in Belfast, I couldn’t help but feel emotional as my own movie theater memories rose to the surface. When Mike and Therese took the stage to give their final speech, the room erupted with applause.

Just before the lights went down, and the movie rolled—the 1971 film The Last Picture Show— Mike ended with this:

I want to tell you about The Last Picture Show. It’s about a small town, drying up, getting ready to die in West Texas. Set in 1951, it has a lot to say about the state of small-town America, especially very small towns, who all had movie theaters back then. But it’s about to change. TV is yet to arrive, but it’s coming. At one point they say, “the movie theaters are dying.” And, you know, it’s true. I have a book called Silent Screens. It shows movie theaters that are now parking lots, rifle ranges, office complexes, swimming pools…. A lot of movie theaters have disappeared. Belfast’s did not. The Colonial Theatre has thrived for more than 70 years since this movie came out, and people are still coming to the movies. Thank you. And while the story is set in a dying town, with a dying movie theater, Belfast is anything but that town. And the Colonial is not that movie theater. So I don’t fear for the future, I know people are sad. I’m sad! But I’m not really sad. I’m so blessed that we did this. It’s been a fantastic thing for me. I love people, I love doing this job. It’s been lucky for me, to be able to do this for 27 years. I love Belfast, I love movies, I love the stories they tell. It doesn’t get any better than that. Thank you guys. That’s it. I won’t be grabbing the microphone anymore, except at council meetings.

The Colonial Theatre won’t be closed for long, of that much Mike and Therese are sure. Who will take it on next and what “secret sauce,” as Mike says, will they bring to it? We’ll just have to wait and see.

It’s a bittersweet feeling to stand in the midst of an ending. The room was packed, and as I sipped my beer I listened to groups of people around me telling their own personal stories of the Colonial. First jobs, first dates, favorite movies …. While I didn’t grow up in Belfast, I couldn’t help but feel emotional as my own movie theater memories rose to the surface. When Mike and Therese took the stage to give their final speech, the room erupted with applause.

Just before the lights went down, and the movie rolled—the 1971 film The Last Picture Show— Mike ended with this:

I want to tell you about The Last Picture Show. It’s about a small town, drying up, getting ready to die in West Texas. Set in 1951, it has a lot to say about the state of small-town America, especially very small towns, who all had movie theaters back then. But it’s about to change. TV is yet to arrive, but it’s coming. At one point they say, “the movie theaters are dying.” And, you know, it’s true. I have a book called Silent Screens. It shows movie theaters that are now parking lots, rifle ranges, office complexes, swimming pools…. A lot of movie theaters have disappeared. Belfast’s did not. The Colonial Theatre has thrived for more than 70 years since this movie came out, and people are still coming to the movies. Thank you. And while the story is set in a dying town, with a dying movie theater, Belfast is anything but that town. And the Colonial is not that movie theater. So I don’t fear for the future, I know people are sad. I’m sad! But I’m not really sad. I’m so blessed that we did this. It’s been a fantastic thing for me. I love people, I love doing this job. It’s been lucky for me, to be able to do this for 27 years. I love Belfast, I love movies, I love the stories they tell. It doesn’t get any better than that. Thank you guys. That’s it. I won’t be grabbing the microphone anymore, except at council meetings.

The Colonial Theatre won’t be closed for long, of that much Mike and Therese are sure. Who will take it on next and what “secret sauce,” as Mike says, will they bring to it? We’ll just have to wait and see.

When you think about it, back then, movie theaters were really the first place that parents would allow their kids to go on their own. Especially in smaller towns—other than church and school, this was it.

What is your memory of the Colonial Theatre before buying it in ’95?

I’ve always been going to the movies. I came to Belfast in the winter of ’79 and opened a bar where the Parent Gallery is. If it was dead, I would say to the waitress, “I’m going to run over and watch a movie.” At that time, there was only one theater and the phone was right by the door. I would tell her, “If it gets busy, just call me and I’ll sit in the back and I’ll hear the phone ring.”

How did you and Therese come to take it over?

At that point I was already an entrepreneur. I had a window cleaning business at the time—this was when the bank MBNA came to Belfast, which was a big, big deal—and they hired my company, so I had a successful thing going with them. I had opened a bar. I had gone to Morocco and started an import business. I opened a gift shop. I was in the middle of developing a tool company, which I still have. So I was pretty good at figuring out how to do something.

Therese went to school for design, so she had all of the artistic sensibilities. What had happened was she had a huge job for the Camden Opera House, where they actually had to stage the entire room and then paint the ceiling. It was a huge project and she had all this work, and then for, like, two months, nothing. Couldn’t find anything. That’s what was happening when I saw the ad and said to her, “Hey, the Colonial Theatre’s for sale. Why don’t we buy it?” That was on a Wednesday. By Friday we had put in an offer.

I’ve always been going to the movies. I came to Belfast in the winter of ’79 and opened a bar where the Parent Gallery is. If it was dead, I would say to the waitress, “I’m going to run over and watch a movie.” At that time, there was only one theater and the phone was right by the door. I would tell her, “If it gets busy, just call me and I’ll sit in the back and I’ll hear the phone ring.”

How did you and Therese come to take it over?

At that point I was already an entrepreneur. I had a window cleaning business at the time—this was when the bank MBNA came to Belfast, which was a big, big deal—and they hired my company, so I had a successful thing going with them. I had opened a bar. I had gone to Morocco and started an import business. I opened a gift shop. I was in the middle of developing a tool company, which I still have. So I was pretty good at figuring out how to do something.

Therese went to school for design, so she had all of the artistic sensibilities. What had happened was she had a huge job for the Camden Opera House, where they actually had to stage the entire room and then paint the ceiling. It was a huge project and she had all this work, and then for, like, two months, nothing. Couldn’t find anything. That’s what was happening when I saw the ad and said to her, “Hey, the Colonial Theatre’s for sale. Why don’t we buy it?” That was on a Wednesday. By Friday we had put in an offer.

Was there any competition?

There were three or four other groups of people, some of them very well off. I called my accountant and said, “Hey I’m thinking of buying the movie theater. You got any advice for me?” And she goes, “Well, I can’t really talk about it. I’m part of a group that’s trying to buy it.” I knew who the group was—very well off people. We were doing OK, but these were real businesspeople. We were faux businesspeople, so to speak. So on that Friday they got four offers.

Who were the owners at that time?

The people who owned it were the Kurson family. They had owned movie theaters all over New England, and by this time they were all old. Now, I was, like, 45, but they were in their 80s. Everybody was hanging on by their fingernails, and this was their last theater. It was a dump. It was rundown, it was dirty. The roof leaked. They finally said “It’s time to go, we need to get this over with.” So anyways, they get four offers on a Friday. They call us up, and say “Here’s what we’re doing. We’re giving you all back your offers. Monday morning by 10:00 give us your best offer.” And what I said to Therese was, “Hon, we’re going to be in this for a long time. It doesn’t matter what we pay for it, to some extent. Do you want to do this? Do you want to run a movie theater?” And the answer was, “Yeah, we really want to run a movie theater.” So we put in our offer on Monday and we got it.

It must have been a little intimidating—knowing where to begin.

People would say, “What are you going to do first?” Well, I’m going to find out where they get the movies.

In this business, you talk directly to every film company. If you want a Disney movie, you talk to Disney, or your booker does it. If I want to play Avatar, I call up Disney and on a phone call I say, “I’ll take it.” I’ll pay you, you’ll send it to me. We’re good. It’s all verbal. There’s no contract. You don’t sign anything for Avatar. Try that with getting your carpets cleaned.

So there was no research, we just had to figure it out. Later, I started a website for theater owners or people who wanted to be theater owners, and for a long time it was very popular.

There were three or four other groups of people, some of them very well off. I called my accountant and said, “Hey I’m thinking of buying the movie theater. You got any advice for me?” And she goes, “Well, I can’t really talk about it. I’m part of a group that’s trying to buy it.” I knew who the group was—very well off people. We were doing OK, but these were real businesspeople. We were faux businesspeople, so to speak. So on that Friday they got four offers.

Who were the owners at that time?

The people who owned it were the Kurson family. They had owned movie theaters all over New England, and by this time they were all old. Now, I was, like, 45, but they were in their 80s. Everybody was hanging on by their fingernails, and this was their last theater. It was a dump. It was rundown, it was dirty. The roof leaked. They finally said “It’s time to go, we need to get this over with.” So anyways, they get four offers on a Friday. They call us up, and say “Here’s what we’re doing. We’re giving you all back your offers. Monday morning by 10:00 give us your best offer.” And what I said to Therese was, “Hon, we’re going to be in this for a long time. It doesn’t matter what we pay for it, to some extent. Do you want to do this? Do you want to run a movie theater?” And the answer was, “Yeah, we really want to run a movie theater.” So we put in our offer on Monday and we got it.

It must have been a little intimidating—knowing where to begin.

People would say, “What are you going to do first?” Well, I’m going to find out where they get the movies.

In this business, you talk directly to every film company. If you want a Disney movie, you talk to Disney, or your booker does it. If I want to play Avatar, I call up Disney and on a phone call I say, “I’ll take it.” I’ll pay you, you’ll send it to me. We’re good. It’s all verbal. There’s no contract. You don’t sign anything for Avatar. Try that with getting your carpets cleaned.

So there was no research, we just had to figure it out. Later, I started a website for theater owners or people who wanted to be theater owners, and for a long time it was very popular.

Do you still run that site?

I sold it.

It’s a great idea.

Well, you know what inspired me? I heard there was a website for Burger King employees and I thought, “Why isn’t there a goddamn one for movie theater owners?” It was very successful for a while, but I never kept up with it. I started too many businesses.

You’re clearly the entrepreneur, but I imagine it was amazing for Therese to have this blank canvas, creatively.

She loved it. We loved it. Finding the carpet, the lighting. It used to be that the outside of the theater was just dog shit brown, with a lighter shade of dog shit brown for accents. So coming up with, “What are we going to do here with colors and design and all that?” Therese just jumped in naturally.

She wasn’t as great with people. I would get these passionate emails—“I came to the theater and this lady was so rude to me.” I go, “She’s my wife. She owns the movie theater and she has no boss and she’s a wild animal. She is beyond my control. She does what she does. I’m really sorry. Here’s two free tickets and you can show up tomorrow and you’ll have the best experience.”

I was thinking about how I’ve used movie theaters in my life, because their role and importance has certainly changed, and changed with the times as well. As a kid, in middle school and in high school, the movie theater was the epicenter of my social life, and, maybe even more so, my love life.

When we started, Friday nights were intense. There’d be a hundred kids, and they didn’t care what the movie was. When you think about it, back then, movie theaters were really the first place that parents would allow their kids to go on their own. Especially in smaller towns—other than church and school, this was it. We were a safe place; we had a payphone across the street. Generations of people had their first dates.

I sold it.

It’s a great idea.

Well, you know what inspired me? I heard there was a website for Burger King employees and I thought, “Why isn’t there a goddamn one for movie theater owners?” It was very successful for a while, but I never kept up with it. I started too many businesses.

You’re clearly the entrepreneur, but I imagine it was amazing for Therese to have this blank canvas, creatively.

She loved it. We loved it. Finding the carpet, the lighting. It used to be that the outside of the theater was just dog shit brown, with a lighter shade of dog shit brown for accents. So coming up with, “What are we going to do here with colors and design and all that?” Therese just jumped in naturally.

She wasn’t as great with people. I would get these passionate emails—“I came to the theater and this lady was so rude to me.” I go, “She’s my wife. She owns the movie theater and she has no boss and she’s a wild animal. She is beyond my control. She does what she does. I’m really sorry. Here’s two free tickets and you can show up tomorrow and you’ll have the best experience.”

I was thinking about how I’ve used movie theaters in my life, because their role and importance has certainly changed, and changed with the times as well. As a kid, in middle school and in high school, the movie theater was the epicenter of my social life, and, maybe even more so, my love life.

When we started, Friday nights were intense. There’d be a hundred kids, and they didn’t care what the movie was. When you think about it, back then, movie theaters were really the first place that parents would allow their kids to go on their own. Especially in smaller towns—other than church and school, this was it. We were a safe place; we had a payphone across the street. Generations of people had their first dates.

I’ll miss doing that kind of stuff—taking care of all these people. I get a lot of emotional juice from providing that and being a part of that.

You witnessed the evolution of entertainment, and the accessibility of streamable content, first hand. How did you keep people coming to the movies?

I can’t even begin to imagine how many hundreds of events we put on outside of showing movies. About a month ago we had Leigh Dorsey here, who was in the Race to Alaska. Do you know about this?

No.

The Race to Alaska starts in Port Townsend, Washington. It’s 760 miles by water, and you can’t have a motor on your vehicle. A couple of years ago, she and her husband did it—16 days of rowing, 12 hours a day. And then she did it again this summer with her sister. Anyway, she lives in Belfast. We had her on stage with the boat, which was 25 feet long.

After we had decided to sell, we were also trying to consciously demonstrate what’s possible here. You can do comedy here, you can do music, you can do movies, poetry, artists—all these different things.

One of the most fun things that we did right up to the pandemic were free family matinees at Christmas. Local businesses would sponsor it, we’d sell a huge amount of concession and, meanwhile, the families would stay around and do their holiday shopping in town rather than go to Bangor or Portland or wherever. Every show would be sold out. It was a lot of fun. We actually got the idea from a theater owner in Kansas. I saw an article about it and called the guy. Movie theater owners love each other as long as they’re 50 miles away.

What will you miss about owning the theater?

I’m remembering a few crazy things we did. Every now and then we would want to see the movie first. We could do it, but we didn’t do it generally speaking because, first off, they deliver it to you in big reels of film. You have to put it on a machine and feed it onto a thing that’s like a big circular platter. Like a turntable on a record player and it has a speed control. It takes time to make it up. Anyway, all these guys really wanted to see the movie Gladiator with Russell Crowe, so they’re hurrying the projectionist who’s making it up. He makes it go too fast, the center pops out, and the whole thing goes flying off into the corner. It’s 5,000 feet of film. So we didn’t get to see Gladiator.

Another time, a big blizzard was coming. So I’m, like, we’re not going to be open, but let’s watch Bullitt, which was a Steve McQueen movie. One of the first incredible car chase movies. It’s meant to be seen on the screen because they have these screaming car chases in San Francisco, down the hills and over the tops of them. So here we are, there’s two feet of snow outside, and it’s just, like, “Anybody want to watch Bullitt? Come on over.” Twenty, twenty-five people showed up.

I’ll miss doing that kind of stuff—taking care of all these people. I get a lot of emotional juice from providing that and being a part of that.

Those shared experiences.

There’s a lot of emotion in a movie theater. Apparently they say we have a ghost. I don’t believe in ghosts, so I don’t buy it. But when you think of all the emotion that people have experienced that is infused into a room, whether it’s anger or love or violence or comedy, we’ve had it. We’ve had it all.

I can’t even begin to imagine how many hundreds of events we put on outside of showing movies. About a month ago we had Leigh Dorsey here, who was in the Race to Alaska. Do you know about this?

No.

The Race to Alaska starts in Port Townsend, Washington. It’s 760 miles by water, and you can’t have a motor on your vehicle. A couple of years ago, she and her husband did it—16 days of rowing, 12 hours a day. And then she did it again this summer with her sister. Anyway, she lives in Belfast. We had her on stage with the boat, which was 25 feet long.

After we had decided to sell, we were also trying to consciously demonstrate what’s possible here. You can do comedy here, you can do music, you can do movies, poetry, artists—all these different things.

One of the most fun things that we did right up to the pandemic were free family matinees at Christmas. Local businesses would sponsor it, we’d sell a huge amount of concession and, meanwhile, the families would stay around and do their holiday shopping in town rather than go to Bangor or Portland or wherever. Every show would be sold out. It was a lot of fun. We actually got the idea from a theater owner in Kansas. I saw an article about it and called the guy. Movie theater owners love each other as long as they’re 50 miles away.

What will you miss about owning the theater?

I’m remembering a few crazy things we did. Every now and then we would want to see the movie first. We could do it, but we didn’t do it generally speaking because, first off, they deliver it to you in big reels of film. You have to put it on a machine and feed it onto a thing that’s like a big circular platter. Like a turntable on a record player and it has a speed control. It takes time to make it up. Anyway, all these guys really wanted to see the movie Gladiator with Russell Crowe, so they’re hurrying the projectionist who’s making it up. He makes it go too fast, the center pops out, and the whole thing goes flying off into the corner. It’s 5,000 feet of film. So we didn’t get to see Gladiator.

Another time, a big blizzard was coming. So I’m, like, we’re not going to be open, but let’s watch Bullitt, which was a Steve McQueen movie. One of the first incredible car chase movies. It’s meant to be seen on the screen because they have these screaming car chases in San Francisco, down the hills and over the tops of them. So here we are, there’s two feet of snow outside, and it’s just, like, “Anybody want to watch Bullitt? Come on over.” Twenty, twenty-five people showed up.

I’ll miss doing that kind of stuff—taking care of all these people. I get a lot of emotional juice from providing that and being a part of that.

Those shared experiences.

There’s a lot of emotion in a movie theater. Apparently they say we have a ghost. I don’t believe in ghosts, so I don’t buy it. But when you think of all the emotion that people have experienced that is infused into a room, whether it’s anger or love or violence or comedy, we’ve had it. We’ve had it all.