Cover Art:“Oui, Chef” by Dominique Ostuni

Cover Art:“Oui, Chef” by Dominique Ostuni 8.5" x 11"

Mixed Media (pastel chalk, oil paint, graphite pencil)

Dominique Ostuni is a multidisciplinary artist out of Bowdoinham, ME. She works across a variety of different mediums — but tends to focus mainly on ceramic objects and collage. Her work can be seen on her instagram and website.

ISSUE ONE

Nov/Dec 2022In Conversation With Gregory Beson: Studio Beson

Food & Family with Frank Giglio: Ararat Farms

Music & Lyrics from Alice Kristiansen: Memos from Maine

In Conversation with Mike Hurley: Belfast’s Colonial Theatre

Creative Away: Travel to Bulgaria with Maine’s Ari Kellerman

Visiting Windsor Chairmakers

SUBSCRIBE

We publish 3 issues a year. Becoming a subscriber is totally free and ensures that you never miss one. Subscribe here.

IN CONVERSATION WITH GREGORY BESON:

STUDIO BESON

Nov/Dec 2022

Interview by Devon Harris

Portraits by Jen Steele

“Tenderness” show photography by John Daniel Powers

Portraits by Jen Steele

“Tenderness” show photography by John Daniel Powers

I first met Gregory Beson at the furniture showroom in Lincolnville where I was working. He was my first sale, taking home a cherry Shaker side chair with a green, woven seat. Gregory lives and works in New York, but has a deep love of Maine, largely born from the time he spent in Blue Hill in his 20s. This past year he bought a plot of land on Vinalhaven Island, on which he plans to make a home.

I met up with Gregory at his studio in Brooklyn, a large, warm, space that smelled of mahogany. Gregory sat in an old, Arts and Crafts–style rocker, and I on a low, deep couch (which he told me later was designed by Hella Jongerius for the UN.) Gregory is soft-spoken, and I leaned forward on my elbows to hear him, praying my mic was picking up his words—many, but carefully chosen. I had questions prepared, but didn’t look at them once. As he told me, he’s been doing very little socializing lately (too busy preparing for his upcoming solo show) and has spent much of the last month in solitude. It felt as if my being there was less for an interview and more as fresh ears for conversations he’s been having with himself for weeks.

But Gregory is anything but self-absorbed, and repeatedly guided our conversation back to the idea of helping others. Were he not a furniture designer, he joked, he’d probably be a high school guidance counselor. For him the draw of Maine is the return to a more collaborative ecosystem. He has many friends there already, and spoke reverently about the many ways in which they support not only each other, but their neighbors and communities.

As we talked, he walked over to his large bookshelf and pulled titles that he thought would interest me. One of them was The Craftsman by Richard Sennett, as he reflected on the etymology of the word craft (from German kraft, meaning strength or power). In New York, he struggles with the tendency for power to be measured in money and status. Through the lens of craft, power is measured by the impact of your work. He refers to this influence as waves—the things we do and make inevitably causing ripples of influence far from our conscious understanding. As he spoke, my eyes drifted to photos of the wave-like ridges on a beach, taped to the wall above a textured, hand-carved side table that will go in his upcoming show—his philosophies literally etched into the material he uses.

When it was time to go, Gregory drove me across the bridge so I wouldn’t have to wait for a Lyft in the rain.

I met up with Gregory at his studio in Brooklyn, a large, warm, space that smelled of mahogany. Gregory sat in an old, Arts and Crafts–style rocker, and I on a low, deep couch (which he told me later was designed by Hella Jongerius for the UN.) Gregory is soft-spoken, and I leaned forward on my elbows to hear him, praying my mic was picking up his words—many, but carefully chosen. I had questions prepared, but didn’t look at them once. As he told me, he’s been doing very little socializing lately (too busy preparing for his upcoming solo show) and has spent much of the last month in solitude. It felt as if my being there was less for an interview and more as fresh ears for conversations he’s been having with himself for weeks.

But Gregory is anything but self-absorbed, and repeatedly guided our conversation back to the idea of helping others. Were he not a furniture designer, he joked, he’d probably be a high school guidance counselor. For him the draw of Maine is the return to a more collaborative ecosystem. He has many friends there already, and spoke reverently about the many ways in which they support not only each other, but their neighbors and communities.

As we talked, he walked over to his large bookshelf and pulled titles that he thought would interest me. One of them was The Craftsman by Richard Sennett, as he reflected on the etymology of the word craft (from German kraft, meaning strength or power). In New York, he struggles with the tendency for power to be measured in money and status. Through the lens of craft, power is measured by the impact of your work. He refers to this influence as waves—the things we do and make inevitably causing ripples of influence far from our conscious understanding. As he spoke, my eyes drifted to photos of the wave-like ridges on a beach, taped to the wall above a textured, hand-carved side table that will go in his upcoming show—his philosophies literally etched into the material he uses.

When it was time to go, Gregory drove me across the bridge so I wouldn’t have to wait for a Lyft in the rain.

I want to talk to you about chairs.

I like using chairs as a vehicle, something everyone can understand. If you have a body, you can understand a chair. It’s anthropomorphic. It looks like a being. It has character. You can project yourself into it— what will I feel sitting in that?

When I was in school, thinking a lot about materials and systems, I designed the bone chair and salt chair so I could use that typology to explore those essentially artistic ideas. I was essentially trying to be a sculptor through chairs, which might have confused the pieces a little bit, but it was where I was at. I haven’t been thinking too much about conceptual chairs lately. Truthfully, I’m a little more interested in how people live day to day. Not that they can’t be artful and poetic, that’s still important to me, but I also really want functional.

I’m teaching a class on chairs at Parsons right now, and the big question is, “What chair should we make right now?” The answer is whatever they make. I don’t know the answer for myself, but what I come back to is more philosophical. My next show is called “Tenderness,” and it’s related to this John Berger writing that says, essentially, that tenderness is a free act. It costs nothing and won’t necessarily give you money. It’s something you choose to do because you want to. So, when making furniture— if it’s functional—there’s always a user. One of the pieces I’m making is a long bench that has a thick cushion made of antique textile. It’s my version of tenderness. It’s not a chair, it’s not a sofa, it’s more transitional. It’s just a bench that is soft and beautiful, where you would put your shoes on, and then go about your day. That moment, that breath, is what I’m interested in.

I like using chairs as a vehicle, something everyone can understand. If you have a body, you can understand a chair. It’s anthropomorphic. It looks like a being. It has character. You can project yourself into it— what will I feel sitting in that?

When I was in school, thinking a lot about materials and systems, I designed the bone chair and salt chair so I could use that typology to explore those essentially artistic ideas. I was essentially trying to be a sculptor through chairs, which might have confused the pieces a little bit, but it was where I was at. I haven’t been thinking too much about conceptual chairs lately. Truthfully, I’m a little more interested in how people live day to day. Not that they can’t be artful and poetic, that’s still important to me, but I also really want functional.

I’m teaching a class on chairs at Parsons right now, and the big question is, “What chair should we make right now?” The answer is whatever they make. I don’t know the answer for myself, but what I come back to is more philosophical. My next show is called “Tenderness,” and it’s related to this John Berger writing that says, essentially, that tenderness is a free act. It costs nothing and won’t necessarily give you money. It’s something you choose to do because you want to. So, when making furniture— if it’s functional—there’s always a user. One of the pieces I’m making is a long bench that has a thick cushion made of antique textile. It’s my version of tenderness. It’s not a chair, it’s not a sofa, it’s more transitional. It’s just a bench that is soft and beautiful, where you would put your shoes on, and then go about your day. That moment, that breath, is what I’m interested in.

…Tenderness is a free act. It costs nothing and won’t necessarily give you money. It’s something you choose to do because you want to.

My sister’s having a baby, so my family just gave her a rocking chair. It stood out to me that the rockers transformed the chair into something so, as you would say, tender. The Shakers also, I believe, originally added rockers to their chairs for the elderly members, who would be similarly comforted by the rocking motion. It’s such a caring approach to furniture-making.

Yeah, empathy embedded in objects. This is where chairs get interesting. There are some people who care too much about a conception of comfort. Everything has cushions. And others who are focused on “functional sculpture,” or “collectible design,” or whatever they might name it —where it almost completely throws function and comfort away and just becomes an “aesthetic,” kind of like what Donald Judd was doing. I made a chair using similar Judd geometry. I sat in it and thought, “This is terrible. This is unkind.” It seems to me, you see people doing these wild “art,” chairs because you don’t have to deal with ergonomics. You’re just dealing with the eye. And if that’s the case, okay. Some of that stuff is interesting. But it’s so much more interesting to hold somebody—, really hold them—rather than just hold their gaze.

Tell me more about your upcoming show.

I’m making 12 pieces. Big pieces and intuitive and gestural pieces, a lot of carvings. I’m trying to be very thoughtful of the materials I’m using and the process and making it more improvisational. It’s an interesting time to come to talk because it’s kind of this transitional moment for me. I don’t know if anybody cares what I’m doing. I care a lot about it and I’m putting my full self into it, but I don’t know if that matters in the work. I know it will matter to certain people, and perhaps that is enough.

Yeah, empathy embedded in objects. This is where chairs get interesting. There are some people who care too much about a conception of comfort. Everything has cushions. And others who are focused on “functional sculpture,” or “collectible design,” or whatever they might name it —where it almost completely throws function and comfort away and just becomes an “aesthetic,” kind of like what Donald Judd was doing. I made a chair using similar Judd geometry. I sat in it and thought, “This is terrible. This is unkind.” It seems to me, you see people doing these wild “art,” chairs because you don’t have to deal with ergonomics. You’re just dealing with the eye. And if that’s the case, okay. Some of that stuff is interesting. But it’s so much more interesting to hold somebody—, really hold them—rather than just hold their gaze.

Tell me more about your upcoming show.

I’m making 12 pieces. Big pieces and intuitive and gestural pieces, a lot of carvings. I’m trying to be very thoughtful of the materials I’m using and the process and making it more improvisational. It’s an interesting time to come to talk because it’s kind of this transitional moment for me. I don’t know if anybody cares what I’m doing. I care a lot about it and I’m putting my full self into it, but I don’t know if that matters in the work. I know it will matter to certain people, and perhaps that is enough.

…In this world where you can get everything you want, how do you have something where you actually have to mean it and want it to get it?

I ask myself that a lot: “If I care, but no one else does, is that enough?”

I think what I’ve realized is it doesn’t really matter. It’s kind of the way I think of my farmer friends. They’re always going to farm. It’s almost like they have to farm. It makes no sense in a capitalist system. You make no money, you beat your body up, and it’s just a hard, hard life. But they’re never not going to do it. Whenever they try not to do it, they just do it again. It’s what they love, and it must be done. I suppose I feel similarly, I’m doing what I must. This summer I did an open studio residency at Haystack and it felt so liberating to get out of my comfort zone. I barely worked in the wood shop. I was doing clay extrusion explorations; I was 3D printing, making paper, drawing while dancing. You could move through ideas very freely with a community of true artists. I’ve always found myself around designers and it’s just a very different thing. The artist’s pursuit, I think, is more about pursuing an idea. Like, I want to really understand this thing—whatever it is. From kind of fun, silly work, to more serious, political work. There are certainly designers who do that, but it’s so easy to get caught up in ego and money as a signifier of success within the design world, not to mention the lack of any real criticism within the field.

It sounds like an amazing communal experience.

You have a group of thoughtful people, and you get free meals all day, and it’s beautiful in and out of the spaces, and you can make and do whatever you want. It’s like a utopian society. I really felt like we could do anything. I’ve never experienced that before. I watched everyone’s skill sets grow because of this trust. It was just an explosion of energy. So many of those people I’ve become good friends with. Nelly’s coming to DJ at the opening of my show. Julie’s helping me glaze the ceramics this week. Paolo and I are planning to collaborate together. I feel like if I got into trouble with the show, there’s probably 10 of them I could call and ask, “Can you come down for two days and help me sand?” And they’d say, “Yeah. We’ll be there.”

I think what I’ve realized is it doesn’t really matter. It’s kind of the way I think of my farmer friends. They’re always going to farm. It’s almost like they have to farm. It makes no sense in a capitalist system. You make no money, you beat your body up, and it’s just a hard, hard life. But they’re never not going to do it. Whenever they try not to do it, they just do it again. It’s what they love, and it must be done. I suppose I feel similarly, I’m doing what I must. This summer I did an open studio residency at Haystack and it felt so liberating to get out of my comfort zone. I barely worked in the wood shop. I was doing clay extrusion explorations; I was 3D printing, making paper, drawing while dancing. You could move through ideas very freely with a community of true artists. I’ve always found myself around designers and it’s just a very different thing. The artist’s pursuit, I think, is more about pursuing an idea. Like, I want to really understand this thing—whatever it is. From kind of fun, silly work, to more serious, political work. There are certainly designers who do that, but it’s so easy to get caught up in ego and money as a signifier of success within the design world, not to mention the lack of any real criticism within the field.

It sounds like an amazing communal experience.

You have a group of thoughtful people, and you get free meals all day, and it’s beautiful in and out of the spaces, and you can make and do whatever you want. It’s like a utopian society. I really felt like we could do anything. I’ve never experienced that before. I watched everyone’s skill sets grow because of this trust. It was just an explosion of energy. So many of those people I’ve become good friends with. Nelly’s coming to DJ at the opening of my show. Julie’s helping me glaze the ceramics this week. Paolo and I are planning to collaborate together. I feel like if I got into trouble with the show, there’s probably 10 of them I could call and ask, “Can you come down for two days and help me sand?” And they’d say, “Yeah. We’ll be there.”

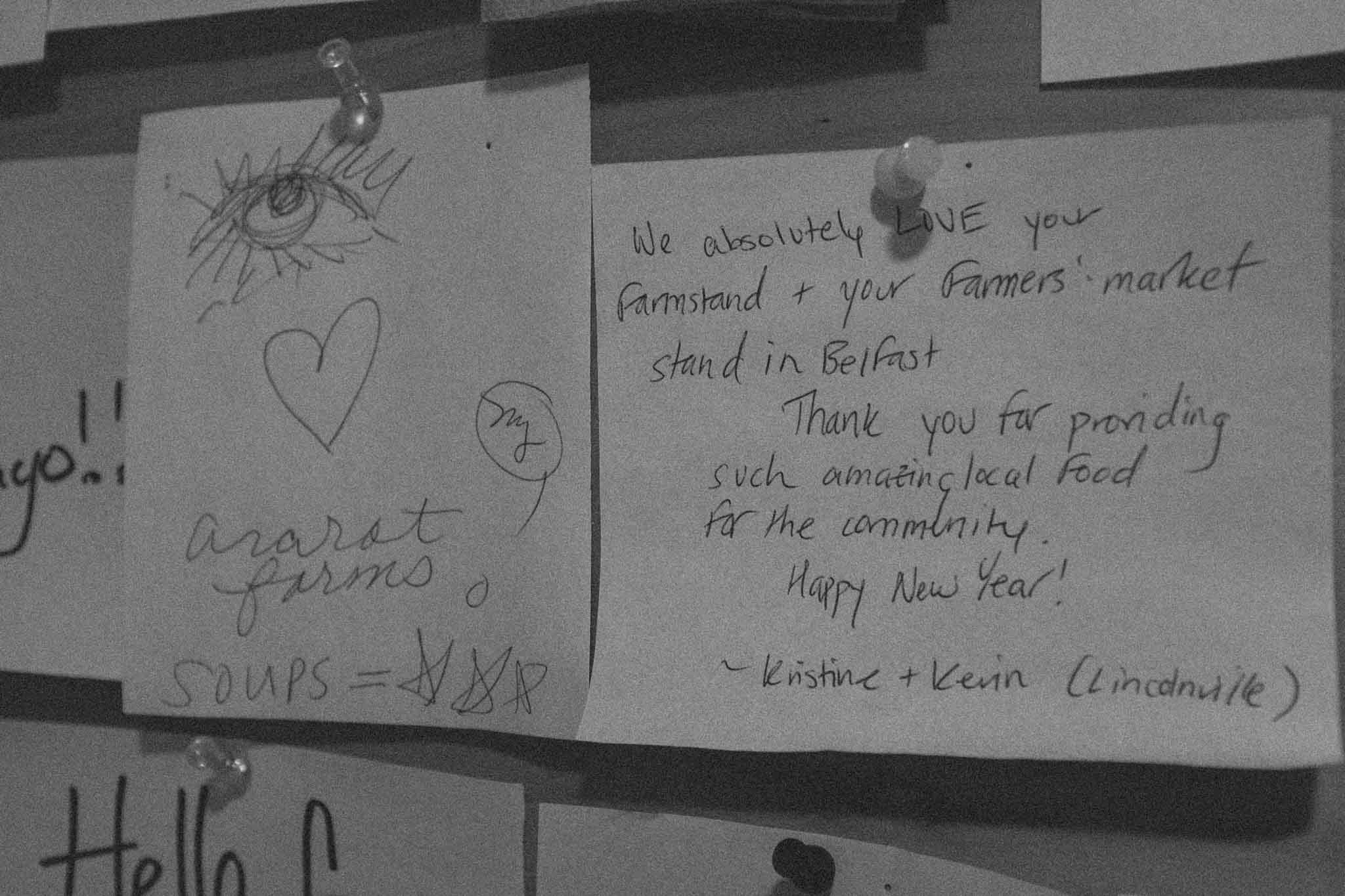

FOOD & FAMILY WITH FRANK GIGLIO: ARARAT FARMS

Nov/Dec 2022Interview and photographs by Devon Harris

Recipe by Frank Giglio

Tucked away in the woods of Lincolnville is Ararat Farms, a small-scale organic farm that supplies its much-loved farmstand with fresh produce, locally sourced meat and dairy products, Maine-grown grains, and fridges full of Frank Giglio’s delicious prepared foods. In true Maine fashion, the farmstand is run on the honor system, and shopping there is an experience in and of itself. If it is possible to feel truly cared for by farmers and a chef you’ve never met, that’s exactly what you feel at Ararat. I caught up with Frank at the commercial kitchen he cooks out of in Belfast, to learn more about the man behind the food I’d been buying almost every day on my way home from work.

What are you making today?

This, here, is an onion miso soup. We grew a few thousand pounds of onions that are storing in our basement now at the farm, so we’ll be doing a lot of onion soups. I made the beef stock yesterday, so I’ll just add the onions and leeks, and then finish it with miso and fresh thyme. This is a two-part carrot situation. I’ll do a harissa-spiced carrot dip and then, with the smaller ones, maybe roast them whole with crumbled feta and some kind of green parsley sauce. This is lemongrass that we grow in the farm’s crop house; I’ll turn that into kombucha. Hummus, white bean dip, curried cashew dip, chicken salad, egg salad. I made chicken liver pâté earlier. I make about 15–20 items for every Saturday market and then split that for the farmstand. Thursdays can be 12-hour days, just cranking things out. Friday is more for entrees and salads.

You’re busy! What do you do on your days off?

Mostly hunt and fish and trap. I’m blessed that I have kids that love doing the things that I enjoy doing. Last year, my 11 year old, Wilder, asked if he could watch a YouTube video about trapping. I was, like, “OK.” I knew nothing about trapping. It was never in the realm of anything I thought I would do. And then he said he wanted to get his trapping license. So, again, I was, like, “OK.” So I got him his license and, because he needs a supervisor, I went through the whole course myself and got mine too. Next thing you know—and luckily my boss has some waterfront land where there are beaver issues—we’re trapping beaver, and my son is skinning it, butchering it, cooking it, everything. He’s doing it all. It’s mind-blowing. Totally mind-blowing.

My younger guy, Sunny, he’s 6, so he’s still a little young, but he’s right there with us. When we’re hunting deer, there are mornings when we’re up at 4, sometimes earlier, getting dressed and going out in the woods. There are days where I’m, like, “Maybe I should let them sleep in.” And then a few hours later they’re bawling their eyes out because I didn’t wake them up. I’m not pressuring them, by any means. It’s, “What do you guys want to do?” They’re, like, “Let’s go fish.”

The way you cook and eat feels very effortful. You’re growing, you’re preserving, you’re hunting. I was going to ask what you get from all of that work, internally. But it just sounds like fun. This is what you guys do for fun.

I don’t need to preserve anything. I have access to coolers full of food at work. I could eat fresh vegetables everyday. I could buy whatever I wanted. But there’s something so fulfilling about doing it yourself. I don’t even know what I would do with my time, if not this. We have beach days in the summer, but if we’re going to go to the beach, why not have a fishing line in the water and maybe catch a fish? I think the pursuit of food just happens to be who I am.

This, here, is an onion miso soup. We grew a few thousand pounds of onions that are storing in our basement now at the farm, so we’ll be doing a lot of onion soups. I made the beef stock yesterday, so I’ll just add the onions and leeks, and then finish it with miso and fresh thyme. This is a two-part carrot situation. I’ll do a harissa-spiced carrot dip and then, with the smaller ones, maybe roast them whole with crumbled feta and some kind of green parsley sauce. This is lemongrass that we grow in the farm’s crop house; I’ll turn that into kombucha. Hummus, white bean dip, curried cashew dip, chicken salad, egg salad. I made chicken liver pâté earlier. I make about 15–20 items for every Saturday market and then split that for the farmstand. Thursdays can be 12-hour days, just cranking things out. Friday is more for entrees and salads.

You’re busy! What do you do on your days off?

Mostly hunt and fish and trap. I’m blessed that I have kids that love doing the things that I enjoy doing. Last year, my 11 year old, Wilder, asked if he could watch a YouTube video about trapping. I was, like, “OK.” I knew nothing about trapping. It was never in the realm of anything I thought I would do. And then he said he wanted to get his trapping license. So, again, I was, like, “OK.” So I got him his license and, because he needs a supervisor, I went through the whole course myself and got mine too. Next thing you know—and luckily my boss has some waterfront land where there are beaver issues—we’re trapping beaver, and my son is skinning it, butchering it, cooking it, everything. He’s doing it all. It’s mind-blowing. Totally mind-blowing.

My younger guy, Sunny, he’s 6, so he’s still a little young, but he’s right there with us. When we’re hunting deer, there are mornings when we’re up at 4, sometimes earlier, getting dressed and going out in the woods. There are days where I’m, like, “Maybe I should let them sleep in.” And then a few hours later they’re bawling their eyes out because I didn’t wake them up. I’m not pressuring them, by any means. It’s, “What do you guys want to do?” They’re, like, “Let’s go fish.”

The way you cook and eat feels very effortful. You’re growing, you’re preserving, you’re hunting. I was going to ask what you get from all of that work, internally. But it just sounds like fun. This is what you guys do for fun.

I don’t need to preserve anything. I have access to coolers full of food at work. I could eat fresh vegetables everyday. I could buy whatever I wanted. But there’s something so fulfilling about doing it yourself. I don’t even know what I would do with my time, if not this. We have beach days in the summer, but if we’re going to go to the beach, why not have a fishing line in the water and maybe catch a fish? I think the pursuit of food just happens to be who I am.

I think the pursuit of food just happens to be who I am.

Is it possible to encourage others, who, say, don’t have this natural inclination towards “the pursuit of food” to be more connected to what they eat?

Years ago I was a raw vegan. I ran marathons and I wore a jersey that said, “Go Vegan” on the back. I cut it out and sewed it on. I had to tell everybody that this is the way that I did it.

Around that time I worked at a health food store and there was another employee there who would just drink Dunkin’ Donuts coffee and smoke cigarettes all day. He would never eat anything in the store unless it was a free sample. I was so mad. I couldn’t tolerate it. But now, I think, “Well, he doesn’t have to. For him, he gets the most joy out of getting on his Harley and going riding for hours. His joy comes from other things and food is just something he thinks about when he’s hungry. And that’s OK.”

I just love working with food. It’s so important to me to make the connections and eat the good food. It’s not even to say I’ll be healthier as a result. I think, for me, I’ve come to learn that health is just a by-product of a more connected lifestyle, and food is just one aspect.

You’re certainly having an impact on how your children look at food. I saw a post of yours where you’re all eating bear fat biscuits with miso gravy and kale microgreens. I’ve cooked for families before where the kids only ate Rice Krispies for dinner. Every night, dry Rice Krispies.

You go to restaurants and they hand you a kids’ menu and it’s, like, “My kids don’t eat off the kids’ menu. They eat off the menu.” If anything, I think I should be eating chicken nuggets and my kids should get the more nutrient-dense foods. They’re growing and developing; they need it way more than me.

It just so happened to be this way, but my son’s first non-breastmilk food was a saguaro cactus fruit smoothie. This fruit is only available for two weeks in the summer, and every desert animal is going for it. It’s amazing. I can’t even describe it because it’s been so long since I’ve had it, but I have this picture of my son with his face covered in this smoothie. We never made baby food. We didn’t buy baby food. I would literally make beef stew and just pre-chew his meat.

It’s funny—sometimes my kid is too much of a food snob now. He’ll be, like, “You should have broiled it instead.” And I’m, like, “Alright, dude, relax.” But I love it. I love that they’re pumped at the fact that I connected with a local game butcher and got a bunch of bear fat and rendered it down to make French fries and tempura mackerel.

Years ago I was a raw vegan. I ran marathons and I wore a jersey that said, “Go Vegan” on the back. I cut it out and sewed it on. I had to tell everybody that this is the way that I did it.

Around that time I worked at a health food store and there was another employee there who would just drink Dunkin’ Donuts coffee and smoke cigarettes all day. He would never eat anything in the store unless it was a free sample. I was so mad. I couldn’t tolerate it. But now, I think, “Well, he doesn’t have to. For him, he gets the most joy out of getting on his Harley and going riding for hours. His joy comes from other things and food is just something he thinks about when he’s hungry. And that’s OK.”

I just love working with food. It’s so important to me to make the connections and eat the good food. It’s not even to say I’ll be healthier as a result. I think, for me, I’ve come to learn that health is just a by-product of a more connected lifestyle, and food is just one aspect.

You’re certainly having an impact on how your children look at food. I saw a post of yours where you’re all eating bear fat biscuits with miso gravy and kale microgreens. I’ve cooked for families before where the kids only ate Rice Krispies for dinner. Every night, dry Rice Krispies.

You go to restaurants and they hand you a kids’ menu and it’s, like, “My kids don’t eat off the kids’ menu. They eat off the menu.” If anything, I think I should be eating chicken nuggets and my kids should get the more nutrient-dense foods. They’re growing and developing; they need it way more than me.

It just so happened to be this way, but my son’s first non-breastmilk food was a saguaro cactus fruit smoothie. This fruit is only available for two weeks in the summer, and every desert animal is going for it. It’s amazing. I can’t even describe it because it’s been so long since I’ve had it, but I have this picture of my son with his face covered in this smoothie. We never made baby food. We didn’t buy baby food. I would literally make beef stew and just pre-chew his meat.

It’s funny—sometimes my kid is too much of a food snob now. He’ll be, like, “You should have broiled it instead.” And I’m, like, “Alright, dude, relax.” But I love it. I love that they’re pumped at the fact that I connected with a local game butcher and got a bunch of bear fat and rendered it down to make French fries and tempura mackerel.

I’ve come to learn that health is just a by-product of a more connected lifestyle, and food is just one aspect.

To me, it feels like kids just want to be a part of what’s happening. So if you can include them in the process, they might be more willing to try what you put in front of them.

Last year we were driving and my kid yelled out, “Holy cow! I think I just saw the biggest chicken of the woods ever!” We pulled over and it was on this huge beech tree. We harvested well over 20 pounds of mushrooms and didn’t even take half of it. I canned a bunch, and now when we eat it, there’s that memory. We talk about that tree and how cool it was that, on this drive to do something else, he spotted it. That’s part of what I enjoy about preservation: that memory recall.

You can certainly recall a dinner that you’ve had out somewhere, but when you hunted that wild turkey yourself, and we’re eating it six months later, and my kid gets to tell the story again, maybe to a guest who’s coming over for dinner, and he gets to share his hunt and his success, and all the things he had to do in order to put it in the freezer, that’s awesome.

My ultimate goal is to get my Maine guide’s license and take people out. Mostly parents with their kids, and be, like, “OK, we went fishing for the day. Now let’s go back home and prepare this food together.”

Last year we were driving and my kid yelled out, “Holy cow! I think I just saw the biggest chicken of the woods ever!” We pulled over and it was on this huge beech tree. We harvested well over 20 pounds of mushrooms and didn’t even take half of it. I canned a bunch, and now when we eat it, there’s that memory. We talk about that tree and how cool it was that, on this drive to do something else, he spotted it. That’s part of what I enjoy about preservation: that memory recall.

You can certainly recall a dinner that you’ve had out somewhere, but when you hunted that wild turkey yourself, and we’re eating it six months later, and my kid gets to tell the story again, maybe to a guest who’s coming over for dinner, and he gets to share his hunt and his success, and all the things he had to do in order to put it in the freezer, that’s awesome.

My ultimate goal is to get my Maine guide’s license and take people out. Mostly parents with their kids, and be, like, “OK, we went fishing for the day. Now let’s go back home and prepare this food together.”

MUSIC & POETRY FROM ALICE KRISTIANSEN:

MEMOS FROM MAINE

Nov/Dec 2022

Alice Kristiansen got her start over a decade ago posting dreamy covers of pop songs on her YouTube channel. By luck (and a very intelligent algorithm), I found her right away, and played her videos on repeat as I did homework in my dorm room. It wasn’t until this last year that I—still following her channel—realized she was also from Maine, just a few hours up the coast.

Nowadays, Alice is known for much more than her covers, and her loyal fanbase devours just about everything she puts out: original songs, photos of her garden, this amazing video of her talking about life as if whoever is listening is already a close friend. And herein lies her magic. Alice’s work is a masterpiece of vulnerability. Her most recent EP, Memos from Maine, was recorded live and in one take. Like her treasured YouTube covers, it is raw, ethereal and dripping with emotion. Take a listen below and then go save it to your Spotify immediately.

When I asked Alice what she would like to share alongside her music, she sent me this poem.

Nowadays, Alice is known for much more than her covers, and her loyal fanbase devours just about everything she puts out: original songs, photos of her garden, this amazing video of her talking about life as if whoever is listening is already a close friend. And herein lies her magic. Alice’s work is a masterpiece of vulnerability. Her most recent EP, Memos from Maine, was recorded live and in one take. Like her treasured YouTube covers, it is raw, ethereal and dripping with emotion. Take a listen below and then go save it to your Spotify immediately.

When I asked Alice what she would like to share alongside her music, she sent me this poem.

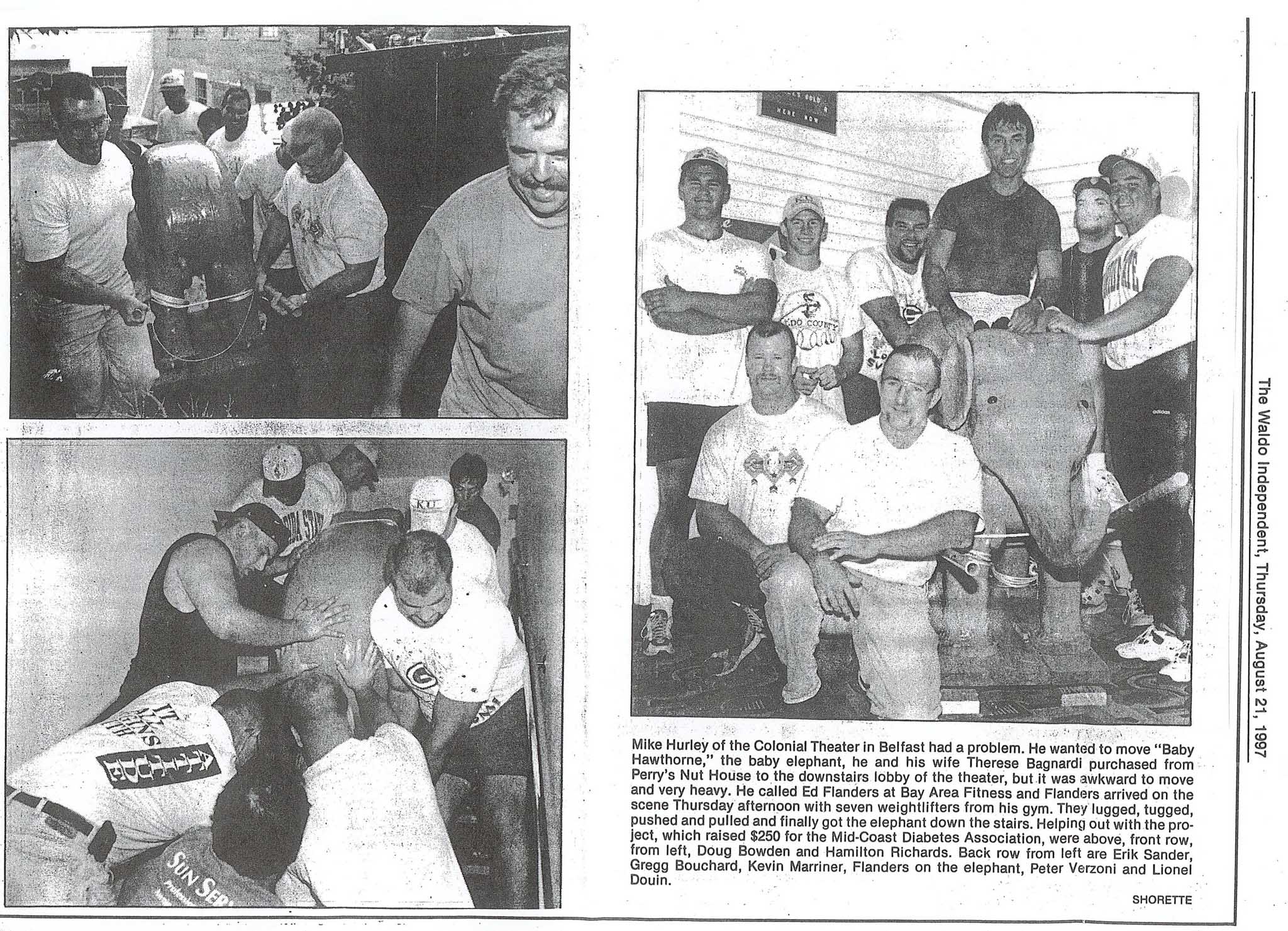

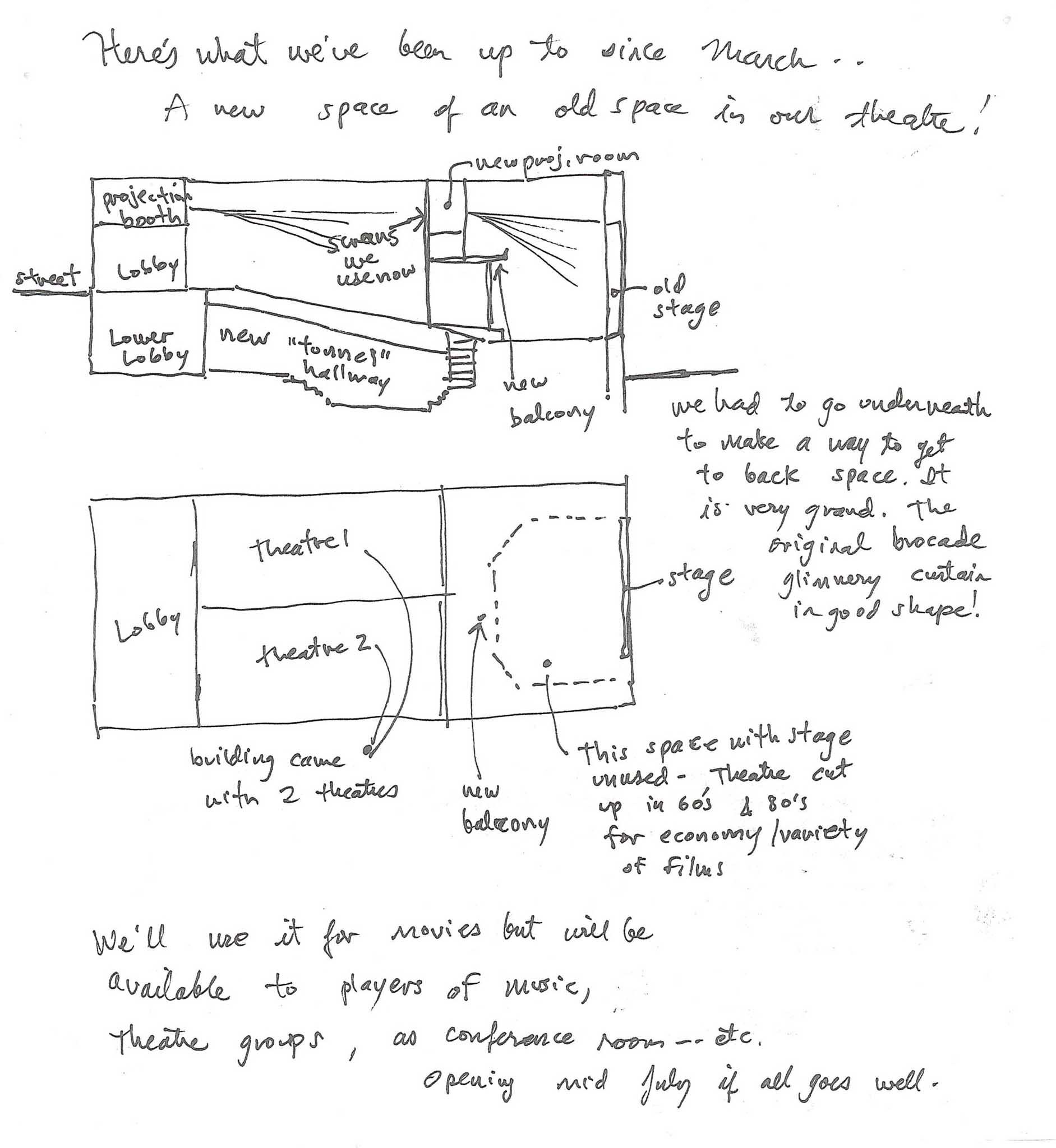

IN CONVERSATION WITH MIKE HURLEY: BELFAST’S COLONIAL THEATRE

Nov/Dec 2022

Interview & Photographs by Devon Harris

Mike Hurley and Therese Bagnardi bought the Colonial Theatre in 1995 and ran it for 27 years before putting it up for sale again this September. I moved to Belfast during the pandemic, when the Colonial—along with most other theaters across the country—was closed to the public. A year later, when I heard of its impending closure, I vowed to make it in for a show while I still could, and ended up at the last showing of the last movie, on the final night of the 10 days of free movies that Mike and Therese closed with.

It’s a bittersweet feeling to stand in the midst of an ending. The room was packed, and as I sipped my beer I listened to groups of people around me telling their own personal stories of the Colonial. First jobs, first dates, favorite movies …. While I didn’t grow up in Belfast, I couldn’t help but feel emotional as my own movie theater memories rose to the surface. When Mike and Therese took the stage to give their final speech, the room erupted with applause.

Just before the lights went down, and the movie rolled—the 1971 film The Last Picture Show— Mike ended with this:

I want to tell you about The Last Picture Show. It’s about a small town, drying up, getting ready to die in West Texas. Set in 1951, it has a lot to say about the state of small-town America, especially very small towns, who all had movie theaters back then. But it’s about to change. TV is yet to arrive, but it’s coming. At one point they say, “the movie theaters are dying.” And, you know, it’s true. I have a book called Silent Screens. It shows movie theaters that are now parking lots, rifle ranges, office complexes, swimming pools…. A lot of movie theaters have disappeared. Belfast’s did not. The Colonial Theatre has thrived for more than 70 years since this movie came out, and people are still coming to the movies. Thank you. And while the story is set in a dying town, with a dying movie theater, Belfast is anything but that town. And the Colonial is not that movie theater. So I don’t fear for the future, I know people are sad. I’m sad! But I’m not really sad. I’m so blessed that we did this. It’s been a fantastic thing for me. I love people, I love doing this job. It’s been lucky for me, to be able to do this for 27 years. I love Belfast, I love movies, I love the stories they tell. It doesn’t get any better than that. Thank you guys. That’s it. I won’t be grabbing the microphone anymore, except at council meetings.

The Colonial Theatre won’t be closed for long, of that much Mike and Therese are sure. Who will take it on next and what “secret sauce,” as Mike says, will they bring to it? We’ll just have to wait and see.

It’s a bittersweet feeling to stand in the midst of an ending. The room was packed, and as I sipped my beer I listened to groups of people around me telling their own personal stories of the Colonial. First jobs, first dates, favorite movies …. While I didn’t grow up in Belfast, I couldn’t help but feel emotional as my own movie theater memories rose to the surface. When Mike and Therese took the stage to give their final speech, the room erupted with applause.

Just before the lights went down, and the movie rolled—the 1971 film The Last Picture Show— Mike ended with this:

I want to tell you about The Last Picture Show. It’s about a small town, drying up, getting ready to die in West Texas. Set in 1951, it has a lot to say about the state of small-town America, especially very small towns, who all had movie theaters back then. But it’s about to change. TV is yet to arrive, but it’s coming. At one point they say, “the movie theaters are dying.” And, you know, it’s true. I have a book called Silent Screens. It shows movie theaters that are now parking lots, rifle ranges, office complexes, swimming pools…. A lot of movie theaters have disappeared. Belfast’s did not. The Colonial Theatre has thrived for more than 70 years since this movie came out, and people are still coming to the movies. Thank you. And while the story is set in a dying town, with a dying movie theater, Belfast is anything but that town. And the Colonial is not that movie theater. So I don’t fear for the future, I know people are sad. I’m sad! But I’m not really sad. I’m so blessed that we did this. It’s been a fantastic thing for me. I love people, I love doing this job. It’s been lucky for me, to be able to do this for 27 years. I love Belfast, I love movies, I love the stories they tell. It doesn’t get any better than that. Thank you guys. That’s it. I won’t be grabbing the microphone anymore, except at council meetings.

The Colonial Theatre won’t be closed for long, of that much Mike and Therese are sure. Who will take it on next and what “secret sauce,” as Mike says, will they bring to it? We’ll just have to wait and see.

When you think about it, back then, movie theaters were really the first place that parents would allow their kids to go on their own. Especially in smaller towns—other than church and school, this was it.

What is your memory of the Colonial Theatre before buying it in ’95?

I’ve always been going to the movies. I came to Belfast in the winter of ’79 and opened a bar where the Parent Gallery is. If it was dead, I would say to the waitress, “I’m going to run over and watch a movie.” At that time, there was only one theater and the phone was right by the door. I would tell her, “If it gets busy, just call me and I’ll sit in the back and I’ll hear the phone ring.”

How did you and Therese come to take it over?

At that point I was already an entrepreneur. I had a window cleaning business at the time—this was when the bank MBNA came to Belfast, which was a big, big deal—and they hired my company, so I had a successful thing going with them. I had opened a bar. I had gone to Morocco and started an import business. I opened a gift shop. I was in the middle of developing a tool company, which I still have. So I was pretty good at figuring out how to do something.

Therese went to school for design, so she had all of the artistic sensibilities. What had happened was she had a huge job for the Camden Opera House, where they actually had to stage the entire room and then paint the ceiling. It was a huge project and she had all this work, and then for, like, two months, nothing. Couldn’t find anything. That’s what was happening when I saw the ad and said to her, “Hey, the Colonial Theatre’s for sale. Why don’t we buy it?” That was on a Wednesday. By Friday we had put in an offer.

I’ve always been going to the movies. I came to Belfast in the winter of ’79 and opened a bar where the Parent Gallery is. If it was dead, I would say to the waitress, “I’m going to run over and watch a movie.” At that time, there was only one theater and the phone was right by the door. I would tell her, “If it gets busy, just call me and I’ll sit in the back and I’ll hear the phone ring.”

How did you and Therese come to take it over?

At that point I was already an entrepreneur. I had a window cleaning business at the time—this was when the bank MBNA came to Belfast, which was a big, big deal—and they hired my company, so I had a successful thing going with them. I had opened a bar. I had gone to Morocco and started an import business. I opened a gift shop. I was in the middle of developing a tool company, which I still have. So I was pretty good at figuring out how to do something.

Therese went to school for design, so she had all of the artistic sensibilities. What had happened was she had a huge job for the Camden Opera House, where they actually had to stage the entire room and then paint the ceiling. It was a huge project and she had all this work, and then for, like, two months, nothing. Couldn’t find anything. That’s what was happening when I saw the ad and said to her, “Hey, the Colonial Theatre’s for sale. Why don’t we buy it?” That was on a Wednesday. By Friday we had put in an offer.

Was there any competition?

There were three or four other groups of people, some of them very well off. I called my accountant and said, “Hey I’m thinking of buying the movie theater. You got any advice for me?” And she goes, “Well, I can’t really talk about it. I’m part of a group that’s trying to buy it.” I knew who the group was—very well off people. We were doing OK, but these were real businesspeople. We were faux businesspeople, so to speak. So on that Friday they got four offers.

Who were the owners at that time?

The people who owned it were the Kurson family. They had owned movie theaters all over New England, and by this time they were all old. Now, I was, like, 45, but they were in their 80s. Everybody was hanging on by their fingernails, and this was their last theater. It was a dump. It was rundown, it was dirty. The roof leaked. They finally said “It’s time to go, we need to get this over with.” So anyways, they get four offers on a Friday. They call us up, and say “Here’s what we’re doing. We’re giving you all back your offers. Monday morning by 10:00 give us your best offer.” And what I said to Therese was, “Hon, we’re going to be in this for a long time. It doesn’t matter what we pay for it, to some extent. Do you want to do this? Do you want to run a movie theater?” And the answer was, “Yeah, we really want to run a movie theater.” So we put in our offer on Monday and we got it.

It must have been a little intimidating—knowing where to begin.

People would say, “What are you going to do first?” Well, I’m going to find out where they get the movies.

In this business, you talk directly to every film company. If you want a Disney movie, you talk to Disney, or your booker does it. If I want to play Avatar, I call up Disney and on a phone call I say, “I’ll take it.” I’ll pay you, you’ll send it to me. We’re good. It’s all verbal. There’s no contract. You don’t sign anything for Avatar. Try that with getting your carpets cleaned.

So there was no research, we just had to figure it out. Later, I started a website for theater owners or people who wanted to be theater owners, and for a long time it was very popular.

There were three or four other groups of people, some of them very well off. I called my accountant and said, “Hey I’m thinking of buying the movie theater. You got any advice for me?” And she goes, “Well, I can’t really talk about it. I’m part of a group that’s trying to buy it.” I knew who the group was—very well off people. We were doing OK, but these were real businesspeople. We were faux businesspeople, so to speak. So on that Friday they got four offers.

Who were the owners at that time?

The people who owned it were the Kurson family. They had owned movie theaters all over New England, and by this time they were all old. Now, I was, like, 45, but they were in their 80s. Everybody was hanging on by their fingernails, and this was their last theater. It was a dump. It was rundown, it was dirty. The roof leaked. They finally said “It’s time to go, we need to get this over with.” So anyways, they get four offers on a Friday. They call us up, and say “Here’s what we’re doing. We’re giving you all back your offers. Monday morning by 10:00 give us your best offer.” And what I said to Therese was, “Hon, we’re going to be in this for a long time. It doesn’t matter what we pay for it, to some extent. Do you want to do this? Do you want to run a movie theater?” And the answer was, “Yeah, we really want to run a movie theater.” So we put in our offer on Monday and we got it.

It must have been a little intimidating—knowing where to begin.

People would say, “What are you going to do first?” Well, I’m going to find out where they get the movies.

In this business, you talk directly to every film company. If you want a Disney movie, you talk to Disney, or your booker does it. If I want to play Avatar, I call up Disney and on a phone call I say, “I’ll take it.” I’ll pay you, you’ll send it to me. We’re good. It’s all verbal. There’s no contract. You don’t sign anything for Avatar. Try that with getting your carpets cleaned.

So there was no research, we just had to figure it out. Later, I started a website for theater owners or people who wanted to be theater owners, and for a long time it was very popular.

Do you still run that site?

I sold it.

It’s a great idea.

Well, you know what inspired me? I heard there was a website for Burger King employees and I thought, “Why isn’t there a goddamn one for movie theater owners?” It was very successful for a while, but I never kept up with it. I started too many businesses.

You’re clearly the entrepreneur, but I imagine it was amazing for Therese to have this blank canvas, creatively.

She loved it. We loved it. Finding the carpet, the lighting. It used to be that the outside of the theater was just dog shit brown, with a lighter shade of dog shit brown for accents. So coming up with, “What are we going to do here with colors and design and all that?” Therese just jumped in naturally.

She wasn’t as great with people. I would get these passionate emails—“I came to the theater and this lady was so rude to me.” I go, “She’s my wife. She owns the movie theater and she has no boss and she’s a wild animal. She is beyond my control. She does what she does. I’m really sorry. Here’s two free tickets and you can show up tomorrow and you’ll have the best experience.”

I was thinking about how I’ve used movie theaters in my life, because their role and importance has certainly changed, and changed with the times as well. As a kid, in middle school and in high school, the movie theater was the epicenter of my social life, and, maybe even more so, my love life.

When we started, Friday nights were intense. There’d be a hundred kids, and they didn’t care what the movie was. When you think about it, back then, movie theaters were really the first place that parents would allow their kids to go on their own. Especially in smaller towns—other than church and school, this was it. We were a safe place; we had a payphone across the street. Generations of people had their first dates.

I sold it.

It’s a great idea.

Well, you know what inspired me? I heard there was a website for Burger King employees and I thought, “Why isn’t there a goddamn one for movie theater owners?” It was very successful for a while, but I never kept up with it. I started too many businesses.

You’re clearly the entrepreneur, but I imagine it was amazing for Therese to have this blank canvas, creatively.

She loved it. We loved it. Finding the carpet, the lighting. It used to be that the outside of the theater was just dog shit brown, with a lighter shade of dog shit brown for accents. So coming up with, “What are we going to do here with colors and design and all that?” Therese just jumped in naturally.

She wasn’t as great with people. I would get these passionate emails—“I came to the theater and this lady was so rude to me.” I go, “She’s my wife. She owns the movie theater and she has no boss and she’s a wild animal. She is beyond my control. She does what she does. I’m really sorry. Here’s two free tickets and you can show up tomorrow and you’ll have the best experience.”

I was thinking about how I’ve used movie theaters in my life, because their role and importance has certainly changed, and changed with the times as well. As a kid, in middle school and in high school, the movie theater was the epicenter of my social life, and, maybe even more so, my love life.

When we started, Friday nights were intense. There’d be a hundred kids, and they didn’t care what the movie was. When you think about it, back then, movie theaters were really the first place that parents would allow their kids to go on their own. Especially in smaller towns—other than church and school, this was it. We were a safe place; we had a payphone across the street. Generations of people had their first dates.

I’ll miss doing that kind of stuff—taking care of all these people. I get a lot of emotional juice from providing that and being a part of that.

You witnessed the evolution of entertainment, and the accessibility of streamable content, first hand. How did you keep people coming to the movies?

I can’t even begin to imagine how many hundreds of events we put on outside of showing movies. About a month ago we had Leigh Dorsey here, who was in the Race to Alaska. Do you know about this?

No.

The Race to Alaska starts in Port Townsend, Washington. It’s 760 miles by water, and you can’t have a motor on your vehicle. A couple of years ago, she and her husband did it—16 days of rowing, 12 hours a day. And then she did it again this summer with her sister. Anyway, she lives in Belfast. We had her on stage with the boat, which was 25 feet long.

After we had decided to sell, we were also trying to consciously demonstrate what’s possible here. You can do comedy here, you can do music, you can do movies, poetry, artists—all these different things.

One of the most fun things that we did right up to the pandemic were free family matinees at Christmas. Local businesses would sponsor it, we’d sell a huge amount of concession and, meanwhile, the families would stay around and do their holiday shopping in town rather than go to Bangor or Portland or wherever. Every show would be sold out. It was a lot of fun. We actually got the idea from a theater owner in Kansas. I saw an article about it and called the guy. Movie theater owners love each other as long as they’re 50 miles away.

What will you miss about owning the theater?

I’m remembering a few crazy things we did. Every now and then we would want to see the movie first. We could do it, but we didn’t do it generally speaking because, first off, they deliver it to you in big reels of film. You have to put it on a machine and feed it onto a thing that’s like a big circular platter. Like a turntable on a record player and it has a speed control. It takes time to make it up. Anyway, all these guys really wanted to see the movie Gladiator with Russell Crowe, so they’re hurrying the projectionist who’s making it up. He makes it go too fast, the center pops out, and the whole thing goes flying off into the corner. It’s 5,000 feet of film. So we didn’t get to see Gladiator.

Another time, a big blizzard was coming. So I’m, like, we’re not going to be open, but let’s watch Bullitt, which was a Steve McQueen movie. One of the first incredible car chase movies. It’s meant to be seen on the screen because they have these screaming car chases in San Francisco, down the hills and over the tops of them. So here we are, there’s two feet of snow outside, and it’s just, like, “Anybody want to watch Bullitt? Come on over.” Twenty, twenty-five people showed up.

I’ll miss doing that kind of stuff—taking care of all these people. I get a lot of emotional juice from providing that and being a part of that.

Those shared experiences.

There’s a lot of emotion in a movie theater. Apparently they say we have a ghost. I don’t believe in ghosts, so I don’t buy it. But when you think of all the emotion that people have experienced that is infused into a room, whether it’s anger or love or violence or comedy, we’ve had it. We’ve had it all.

I can’t even begin to imagine how many hundreds of events we put on outside of showing movies. About a month ago we had Leigh Dorsey here, who was in the Race to Alaska. Do you know about this?

No.

The Race to Alaska starts in Port Townsend, Washington. It’s 760 miles by water, and you can’t have a motor on your vehicle. A couple of years ago, she and her husband did it—16 days of rowing, 12 hours a day. And then she did it again this summer with her sister. Anyway, she lives in Belfast. We had her on stage with the boat, which was 25 feet long.

After we had decided to sell, we were also trying to consciously demonstrate what’s possible here. You can do comedy here, you can do music, you can do movies, poetry, artists—all these different things.

One of the most fun things that we did right up to the pandemic were free family matinees at Christmas. Local businesses would sponsor it, we’d sell a huge amount of concession and, meanwhile, the families would stay around and do their holiday shopping in town rather than go to Bangor or Portland or wherever. Every show would be sold out. It was a lot of fun. We actually got the idea from a theater owner in Kansas. I saw an article about it and called the guy. Movie theater owners love each other as long as they’re 50 miles away.

What will you miss about owning the theater?

I’m remembering a few crazy things we did. Every now and then we would want to see the movie first. We could do it, but we didn’t do it generally speaking because, first off, they deliver it to you in big reels of film. You have to put it on a machine and feed it onto a thing that’s like a big circular platter. Like a turntable on a record player and it has a speed control. It takes time to make it up. Anyway, all these guys really wanted to see the movie Gladiator with Russell Crowe, so they’re hurrying the projectionist who’s making it up. He makes it go too fast, the center pops out, and the whole thing goes flying off into the corner. It’s 5,000 feet of film. So we didn’t get to see Gladiator.

Another time, a big blizzard was coming. So I’m, like, we’re not going to be open, but let’s watch Bullitt, which was a Steve McQueen movie. One of the first incredible car chase movies. It’s meant to be seen on the screen because they have these screaming car chases in San Francisco, down the hills and over the tops of them. So here we are, there’s two feet of snow outside, and it’s just, like, “Anybody want to watch Bullitt? Come on over.” Twenty, twenty-five people showed up.

I’ll miss doing that kind of stuff—taking care of all these people. I get a lot of emotional juice from providing that and being a part of that.

Those shared experiences.

There’s a lot of emotion in a movie theater. Apparently they say we have a ghost. I don’t believe in ghosts, so I don’t buy it. But when you think of all the emotion that people have experienced that is infused into a room, whether it’s anger or love or violence or comedy, we’ve had it. We’ve had it all.

CREATIVE AWAY:

TRAVEL TO BULGARIA WITH MAINE’S ARI KELLERMAN

Nov/Dec 2022

Photography by Ari Kellerman

Ari Kellerman (@arikellerman) is a New England fine art photographer specializing in still lifes, interiors, portraits, travel, and product photography.

Below is a selection of photos from her most recent travels to Bulgaria.

Below is a selection of photos from her most recent travels to Bulgaria.

WINDSOR CHAIRMAKERS

Nov/Dec 2022

2596 Atlantic Hwy

Lincolnville, Maine

(207) 789-5188

Lincolnville, Maine

(207) 789-5188

There is a quiet joy that comes with the approach of winter; a settling, an appreciation of shorter lines and less traffic, the putting on of favorite sweaters.. There is also a reluctant goodbye to the contagious energy of the “busy months,” and the delight it brings to see friends and customers — some of whom have been coming for decades — each year returning with new guests, children, and grand-children to experience Windsor Chairmakers for themselves.

It is a small team of us here, 13 in total, and every person plays an integral role in our operation. Not only with what they can make with their hands, but also in how they interact with the many visitors we show through our doors. While most come to look at the finished pieces displayed in our showroom, many are equally excited to walk through the shop, talk with our crew as they work, share photos of their own wood-crafting, toss the ball with Sitka, and be, for a moment, surrounded by the hum and sawdust of a busy, working woodshop.

Windsor Chairmakers has been hand-crafting custom, traditional, American furniture for over 35 years out of our shop and showroom in Lincolnville, Maine.

With a commitment to quality that will last generations, our small crew ensures that every piece is made to your exact specifications– working with you every step of the way from its design to its finish.

Photography by Ari Kellerman

Pictured above, Daniel Casburn working on a Windsor Hoopback Sidechair